When I was very young, my interest in family history encompassed people I knew who were still alive; I wondered what they were like as children, teenagers, young married people. My sisters, cousins, and I would sit on the green tweed sofa in my grandfather’s den, looking through the albums of oddly tinted black-and-white and sepia-colored photos by the yellow glow of the floor lamp. It was an evening ritual any time we gathered at the house on the lower Eastern Shore. There weren’t any pictures of William Walsh, my grandfather’s maternal grandfather, only a vague impression of his place in the family tree and the knowledge that he was our most recent immigrant from across the ocean. This made him, to me, the most mysterious and fascinating of our known ancestors. The shades and atmospheres conjured up by my childish imagination gathered around a few details, only half-remembered by those who shared them with me, which I hoarded like shards of blue beach glass. I heard as a child that William, born in 1840, left England as a teenager, and that he had served in the British Navy. That he had “jumped ship” in Virginia. I imagined a skinny kid with light brown hair, looking vaguely like me, literally leaping from the deck of a wooden ship into the salty waves far below. He wasn’t dressed in a naval uniform, but more in the manner of a pirate’s apprentice, in tattered homespun, without shoes, of course. He looked like he belonged among my grandmother’s “rogue’s gallery,” her collection of Royal Doulton toby jugs depicting salty sea characters such as “The Falconer”, “Captain Hook”, and “The Poacher.” I imagined that he had bravely fled an oppressive existence in a crowded and dirty city somewhere, that maybe he was an orphan or even a criminal who had happened to fall from the deck of a ship like a ripe banana onto the remote beach where he would meet my great-greatgrandmother as she sat mending fishing nets, or waded with her skirts hiked up, raking for clams in the shallows.

Decades later, when I was in my mid-thirties, I became seriously interested in delving into the real history of my family. The story I pieced together from the documents of the time told a much different story of William’s arrival in the United States. In 1858, when he was eighteen and a new resident of New York City, he declared his intention to become a U.S. Citizen. Before doing so, however, he needed to establish himself well enough to find a person to attest to his good character. In the meantime, he spent at least part of his time earning a living with the British Merchant Marines. He did indeed “jump ship” in 1864, but in New York, at the height of the Civil War, after the deadly 1863 draft riots but shortly before the Copperheads’ attempt to burn the city to the ground in November of ’64.

When I was a teenager, my father started doing genealogical research, visiting courthouses and local libraries in the small rural places where my grandparents, and their parents, grew up. There was one document he was never able to find: a record of the marriage of William Walsh and my great-great-grandmother, Maggie Ewell. There were rumors of “another family” in New York. These questions were left hanging in the air. It was said that he had a large personality, and was a drinker; that often when he came home in an inebriated state, his wife would yell for their daughters (“the girls”) to all go out in the back yard to be out of the way. These rumors of a double life took root in my imagination. I imagined Maggie, my greatgreat-grandmother, waiting by her kitchen window in Seaside Virginia, wondering when William would be back from his latest jaunt to New York. I imagined her wondering what he was doing, perhaps seething silently about her secret status as the “other woman” while posing as the respectable wife of a hard-working man who occasionally “went to sea,” but was in reality a mysterious foreigner who lied and had shady dealings with mysterious parties far away. I imagined children springing into being in separate families in separate states, with “wives” quietly hating each other across the miles, never guessing that the New York wife had probably died, along with the infant Willie, leaving William to start over as a widower with two young children in the nation’s largest city.

I don’t know what rumor of opportunity, or lucky acquaintanceship formed at the docks or in a neighborhood pub led William to leave New York for Accomack County and the tiny town of Modest Town, and I probably never will. One of his neighbors in the North Moore Street tenement where he lived with Mary was a man from Virginia whose wife had been born in England. Maybe the two men struck up a friendship. I am in awe of the millions of invisible chances and choices, breaths of air on invisible spider’s webs, hormonal fluctuations, desperate situations, and quirks of time and timing which result in each one of us being born.

'Hey! --- Do you have a pic somewhere of our ancestor Walsh the sea captain with the parrot??? '

-email from my cousin

It’s funny, but not difficult to understand, how in the space of four generations, a person within the range of “ordinary” during his or her time and place could accumulate the status of a folk hero. Four generations of imaginative children, listening to snippets of adult conversations after dinner or while half-asleep in their grandparents’ laps, combining them with favorite storybooks, the simplified history learned in school, and artifacts looking down from shelves in their grandfathers’ studies, can give the images that form in their minds a life of their own. He may not have been a sea captain, but there was a parrot. What my cousin knew, he heard from his mother. She had inherited his parrot, which he had stuffed after it died. My cousin’s father, her former husband, had thrown it away without telling her. My cousin had been told that William was on a ship that sailed out of Liverpool, that he made a small fortune seafaring, and that he used that fortune to launch his businesses in the U.S. He retired, or possibly ran from, sea life fairly early. My cousin admitted that it could all have been fabrication, although it now seems like an exaggeration based on truth.

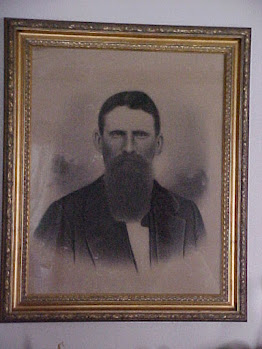

The most compelling story of Mr. Walsh that I’ve seen to date is one that I haven’t yet finished compiling, and it consists of pages of snippets from the ‘News from the Towns’ section of the Peninsula Enterprise newspaper, between the years 1883 and 1915, the year of William’s death. It tells of a busy and enterprising man who operated a store and drinking establishment; raised nine children (two from his previous marriage) with his wife; bought and sold real estate, and generally had his finger in many pots; entertained eccentric visitors from New York and England; invented a hog cholera remedy and a life-saving device for rescuing shipwreck survivors; had many friends and some enemies; traveled frequently with his wife, friends, and children; and once caught a 10-foot shark with a sea turtle in its belly. I do have a photo of him now, taken on one of his trips to England after the death of his wife. It depicts a healthy, well-dressed older man, and carries his signature on the mat---- the same signature that appears on his citizenship papers.

1753

.jpg)